I submitted three paintings in the Midlands Open Exhibition 2011 at Tarpey Gallery, Castle Donington.

This is the one they chose to show.

Opening night is Saturday 12 November 6 - 8 pm.

and after that, opening hours are Wednesday to Saturday 11am to 6pm

77 HIGH STREET, CASTLE DONINGTON, DE742PQ

http://tarpeygallery.com/index.php/art/

A blog about abstract painting (mostly exploring visual ideas through my own sketches and notes)

Saturday, 12 November 2011

Tuesday, 1 November 2011

Concerning the Spiritual in Art - There's a Wasteland to Confont!

I keep coming across statements about abstraction and spirituality. Sean Scully seems to like the connection, and I have been re-reading Concerning the Spiritual in Art by Wassily Kandinsky.

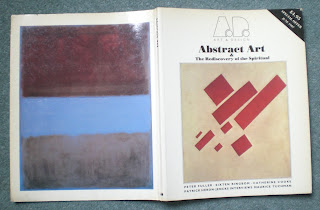

I also found an old copy of Art & Design from 1987, inspired by the exhibition The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890 - 1985 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The Art and Design special is entitled Abstract Art & the Rediscovery of the Spiritual. It has a good article by Catherine Cooke about Kandinsky, an interview with Maurice Tuchman (the curator of the L.A. exhibition) by Charles Jencks and an article by Sixten Ringbom. They are all going on about Theosophy, occultism and mysticism, and suddenly there is this brilliant article by Peter Fuller, who unsurprisingly is rather scathing about it all. It's not the spiritual as such that he is scathing about, but rather its trivialisation and the exhibition's uncritical and unhistorical treatment of its theme: "Tuchman's concept of the spiritual seems so elastic that it could be extended to include any artist he chose - even that vandal Marcel Duchamp, beatified in this show because of his interest in auras and alchemy". I love Fuller's polemical style, I can hear him almost spitting as he says

In other parts of his essay, Fuller puts the label 'scholar' in inverted commas!

The sentence quoted forms a fulcrum in Fullers article, as he now goes on to analyse the state of spiritual life in Europe soon after the turn of the century, positioning Kandinsky's desire to penetrate beyond the veil of material things in relation to Kandinsky's Christian beliefs. Beginning his survey with the natural theology of P.T. Forsyth who insisted that "A distant God, an external God, who from time to time interferes in Nature or the soul, is not a God compatible with Art, nor one very good for piety" he observes that by the time Forsyth was writing, this belief in the immanence of God within his world had already been eroded by the advance of science, secularism and industrialisation. Nature had already become a wasteland, a wilderness divorced from spiritual and aesthetic life. Whilst Kandinsky, brought up in the Eastern, Orthodox tradition with its icons that expressed 'transfigured' rather than visible realities, hoped to see through the physical world to the spirit, earlier Western theologians like John Henry Newman, had already highlighted the gulf that divided the material from the spiritual. What Newman and Kandinsky shared, however, was a 'longing after that which we do not see', a longing that was not shared by the prevailing liberal Protestantism of the Christian churches in pre-war Germany. It is against this backdrop that Kandinsky was attracted to the 'new Christianity' of Theosophy.

Fuller sees patterns that connect Kandinsky's rejection of the worldliness and reasonableness of nineteenth century faith to Rudolf Otto, the Austrian theologian who wrote The Idea of the Holy, and who drew a comparison between the religious experience of 'the numinous' and the aesthetic experience of the beautiful. He probably had Chinese painting in mind when he praised pictures "connected with contemplation - which impress the observer with the feeling that the void itself is depicted as a subject", the void of negation "that does away with every 'this' and 'here' in order that the 'wholly other' may become actual".

Continuing his survey of the spiritual in art against the theological background of the early twentieth century, Fuller observes that the aesthetic rooted in natural theology ended in the obsessively detailed materiality of the Pre-Raphaelites and the hope that abstraction might reveal transcendent reality, ended with the emptiness of the void. In other words we arrive at the impossibility of the spiritual in art.

This impossibility was voiced by the twentieth century's greatest theologian Karl Barth, in his commentary on the Epistle to the Romans. In Barth's theology God is the subject, not the object of experience, and religion is the very antithesis of the (partial) revelation of God in the person of Jesus Christ. Otto's idea of the holy as the wholly other within human experience was the opposite of Barth's 'Wholly Other' as utterly transcendent "the pure and absolute boundary... distinguished qualitatively from men and from everything human, and must never be identified with anything which we name, or conceive, or worship, as God." The most that art (or theology) can ever hope to do is perhaps to point to the revelation of God in Christ, like John the Baptist in Grunwald's Isenheim altarpiece. For Barth, Kandinsky's desire to give expression to the Wholly Other in a plastic way would have been absurd, vain and presumptuous.

Doesn't Barthian theology lead so easily to atheism? It is a very small step from the almost impossibility of experiencing God, to Death of God Theology: we do not live in a garden made by God for people, but in a god-forsaken wasteland, already attested to by many poets and painters of the mid nineteenth century. Fuller puts it this way:

I also found an old copy of Art & Design from 1987, inspired by the exhibition The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890 - 1985 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The Art and Design special is entitled Abstract Art & the Rediscovery of the Spiritual. It has a good article by Catherine Cooke about Kandinsky, an interview with Maurice Tuchman (the curator of the L.A. exhibition) by Charles Jencks and an article by Sixten Ringbom. They are all going on about Theosophy, occultism and mysticism, and suddenly there is this brilliant article by Peter Fuller, who unsurprisingly is rather scathing about it all. It's not the spiritual as such that he is scathing about, but rather its trivialisation and the exhibition's uncritical and unhistorical treatment of its theme: "Tuchman's concept of the spiritual seems so elastic that it could be extended to include any artist he chose - even that vandal Marcel Duchamp, beatified in this show because of his interest in auras and alchemy". I love Fuller's polemical style, I can hear him almost spitting as he says

Tuchman... plunges us immediately into the sterile world of tarot cards, Ouija boards, Dr Who, seances and every kind of mixed-up media. Predictably, neither the catalogue nor the exhibition itself contains any hint of the fact that modern physics and mathematics are generating 'cosmic imagery' of a beauty and power never before seen. Rather the exhibition seems to want to root its credibility in the fact that Kandinsky and Mondrian were interested in Theosophy and Anthroposophy. And sadly, neither Tuchman nor his panel of spiritualistic scholars attempt to understand these artists' involvement with such sects in terms of the state of spiritual life in Europe soon after the turn of the century

In other parts of his essay, Fuller puts the label 'scholar' in inverted commas!

The sentence quoted forms a fulcrum in Fullers article, as he now goes on to analyse the state of spiritual life in Europe soon after the turn of the century, positioning Kandinsky's desire to penetrate beyond the veil of material things in relation to Kandinsky's Christian beliefs. Beginning his survey with the natural theology of P.T. Forsyth who insisted that "A distant God, an external God, who from time to time interferes in Nature or the soul, is not a God compatible with Art, nor one very good for piety" he observes that by the time Forsyth was writing, this belief in the immanence of God within his world had already been eroded by the advance of science, secularism and industrialisation. Nature had already become a wasteland, a wilderness divorced from spiritual and aesthetic life. Whilst Kandinsky, brought up in the Eastern, Orthodox tradition with its icons that expressed 'transfigured' rather than visible realities, hoped to see through the physical world to the spirit, earlier Western theologians like John Henry Newman, had already highlighted the gulf that divided the material from the spiritual. What Newman and Kandinsky shared, however, was a 'longing after that which we do not see', a longing that was not shared by the prevailing liberal Protestantism of the Christian churches in pre-war Germany. It is against this backdrop that Kandinsky was attracted to the 'new Christianity' of Theosophy.

Fuller sees patterns that connect Kandinsky's rejection of the worldliness and reasonableness of nineteenth century faith to Rudolf Otto, the Austrian theologian who wrote The Idea of the Holy, and who drew a comparison between the religious experience of 'the numinous' and the aesthetic experience of the beautiful. He probably had Chinese painting in mind when he praised pictures "connected with contemplation - which impress the observer with the feeling that the void itself is depicted as a subject", the void of negation "that does away with every 'this' and 'here' in order that the 'wholly other' may become actual".

Continuing his survey of the spiritual in art against the theological background of the early twentieth century, Fuller observes that the aesthetic rooted in natural theology ended in the obsessively detailed materiality of the Pre-Raphaelites and the hope that abstraction might reveal transcendent reality, ended with the emptiness of the void. In other words we arrive at the impossibility of the spiritual in art.

This impossibility was voiced by the twentieth century's greatest theologian Karl Barth, in his commentary on the Epistle to the Romans. In Barth's theology God is the subject, not the object of experience, and religion is the very antithesis of the (partial) revelation of God in the person of Jesus Christ. Otto's idea of the holy as the wholly other within human experience was the opposite of Barth's 'Wholly Other' as utterly transcendent "the pure and absolute boundary... distinguished qualitatively from men and from everything human, and must never be identified with anything which we name, or conceive, or worship, as God." The most that art (or theology) can ever hope to do is perhaps to point to the revelation of God in Christ, like John the Baptist in Grunwald's Isenheim altarpiece. For Barth, Kandinsky's desire to give expression to the Wholly Other in a plastic way would have been absurd, vain and presumptuous.

Doesn't Barthian theology lead so easily to atheism? It is a very small step from the almost impossibility of experiencing God, to Death of God Theology: we do not live in a garden made by God for people, but in a god-forsaken wasteland, already attested to by many poets and painters of the mid nineteenth century. Fuller puts it this way:

The importance of Barth lies in the fact that his is the only possible theology for the twentieth century: and it proves to be impossible.He criticises the exhibition for its shallowness and ignorance arguing that the spiritual insights of Tuchman and friends are so thin, and the trance sessions and cosmic vibrations such a distraction, "that they appear not to realise that there is a wasteland to confront." He goes on to list British and Australian artists of the twentieth century of whom this cannot be said (even though they do not feature in the exhibition): Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland, John Piper, Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, Bryan Winter, John Craxton,William Scott, Ivon Hitchens, Alan Davie, David Bomberg,Petter Lanyon, Patrick Heron and Mary Potter. And he closes with an appreciation of "the greatest American painter of the twentieth century" who was "intimately concerned with the bleakness of our spirituality in the absence of God" namely, Mark Rothko.

Friday, 8 July 2011

optical mixing and after images

Some optical mixing goes on when you look at this painting I completed recently, and also subjective colouring that I think is more to do with after images than mixture.

Any blues and/or greens that you see here are subjective, you put them there optically. Physically any 'green' is yellow and any 'blue' is white.

Also do you notice how the red square in the centre looks redder than the other reds? It is the effect of colour contrast as physically it is the same as any of the other reds.

We know about this stuff already. Maybe it is childish of me to continue to be so fascinated by these subjective constructions.

Any blues and/or greens that you see here are subjective, you put them there optically. Physically any 'green' is yellow and any 'blue' is white.

Also do you notice how the red square in the centre looks redder than the other reds? It is the effect of colour contrast as physically it is the same as any of the other reds.

We know about this stuff already. Maybe it is childish of me to continue to be so fascinated by these subjective constructions.

Friday, 1 July 2011

Salt and Ikonography

The photo-realist paintings of John Salt have something approaching the miraculous about them. Could they really be paintings? Pictures of photographs of cars, made with airbrush, they look untouched by human hands.

In the Greek Orthodox tradition acheiropoieta is the name given to icons not made by human hands. They were allegedly painted by saints, or they appeared miraculously like Veronica's Veil or the Turin shroud. Maybe the images were made of the salt from Jesus' sweat.

But these are no icons, though my eye was conned from time to time into thinking that I was looking at very large photographs rather than paintings. In some senses they are not even images, the matter of fact way in which they are produced and presented, renders them artless, real, objects, to be viewed but not worshipped. And in that they are also images, they are images of images, the subject matter of which is artless, found, material as opposed to image in the sense of advertisement, shiny gleaming mirror. Other photo-realists seem more interested in images of this kind.

Ikon Gallery Birmingham is showing work by John Salt until 17 July 2011. I wandered through the two rooms of paintings, 18 in all, spanning 42 years of Salt's artistic output. Not wishing to be impressed (my mission, you may remember, is to view abstract paintings outside of London), I found myself confronted by a body of work that I was hugely impressed by.

I lingered longest on the 2001 painting Tree, a solitary vehicle, parked outside a disused store, next to a weedy self-seeded tree, the long shadows suggesting evening or morning.I feel it should be evening symbolically, but seeing how the windscreen is condensed it looks like it may be morning. The shadows emphasise the whereabouts of the cables running up the side of the building and bring attention to the puny tree, projecting a larger than life image of it onto the façade of the building, rather like the projected image of a photograph onto a large canvas, the standard technique for drawing in photo-realist art. The car and the store are a similar colour, terracotta, or rust. I think it highly unlikely that Salt is interested in the symbolic or metaphoric elements in the piece, and maybe these also are projections, but I find it difficult not to see in the terracotta, a symbol of rust and decay, also hinted at in the parked or abandoned car. And I find it difficult not to see in the tree at least a gesture of hope, however futile. I feel sure that this is not the content of the picture as far as the artist is concerned. However, I think the NLP mantra 'the meaning of a communication is the response you receive rather than the intention you had for it' applies here.

I found I could also interpret the painting in abstract 'colour-field' terms, enjoying the large expanse of orange, framed above by the light blue band of sky, and below by the darker blue/grey of the tarmac. Then becoming aware of the lemon yellow rectangle on the right hand edge, echoed by the adjacent dark grey or black rectangle of the door, within which is a cut-out of white. At the opposite side, there are similar rectangles in almost complementary colours of blue and lilac. In this reading of the painting the car plays almost no role at all. I realise that here I may have been compensating for the abstract paintings I did not find!

There are 18 paintings on view, shown more or less in chronological order, the first room with earlier work, paintings with images taken from catalogues, close-up cars, monochromes in red like Bride 1969, or grey like Sports Wagon 1969, the open door or window creating a frame through which to view the interior, and then the car wrecks of the early 70s: Falcon (Patchwork Surface) 1971, Desert Wreck, 1972; Pontiac with Tree Trunk, 1973. The second room has the more recent works, from the eighties to the present day, vehicles now more abandoned than wrecked, and shown in landscapes, usually a car or caravan, in its immediate surroundings.

At first I was frustrated at being unable to find much evidence of paint being worked or the artist's touch. I thought I had found actual brush-strokes in Falcon (Patchwork Surface). Did I have the impression here that the artist actually enjoyed painting the surface? Then, I realised that the the surface being worked was the car body, with spray-painted graffiti. Those painted gestures looked like they had been enjoyed! And then photographed and then painted, or rather airbrushed. I attempted to inspect the canvas edges for evidence of painterliness, only to be thwarted by the aluminium frames, tight to the stretcher.

Then, once I had resolved to stop messing about looking far what wasn't there and to enjoy the work for what it was, the first thing I noticed was the calm. Galleries are not noisy places, but these works seemed to elicit a quietness that was more than gallery quiet alone. I think it was my emotional state, rather than the physical environment. The paintings are still, still lives in a way, yet they are also memento mori, or as Dieter Roelstraete says in the gallery booklet "that type of still life that is much more eloquently rendered as nature morte". The Car not as status symbol,shiny and triumphant, but as wrecked, decaying, lonely or abandoned.

Although, according to the booklet, Salt claims not to be offering any social comment I agree with Roelstraete that it is difficult not to find here a comment on capitalism and its future. What I don't find is anything about imagined alternatives. I think I read somewhere in Zizek the criticism that we find it easier to imagine the destruction of the planet than we do to imagine a future alternative to global capitalism.

(John Salt, curated by Jonathan Watkins and Diana Stevenson, is showing at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, UK, until 17 July 2011)

| |

| Tree 2001, Casin on linen, 109 x 166 cm, Tellenbach Collection, Switzerland, Image courtesy,of Ikon gallery |

In the Greek Orthodox tradition acheiropoieta is the name given to icons not made by human hands. They were allegedly painted by saints, or they appeared miraculously like Veronica's Veil or the Turin shroud. Maybe the images were made of the salt from Jesus' sweat.

But these are no icons, though my eye was conned from time to time into thinking that I was looking at very large photographs rather than paintings. In some senses they are not even images, the matter of fact way in which they are produced and presented, renders them artless, real, objects, to be viewed but not worshipped. And in that they are also images, they are images of images, the subject matter of which is artless, found, material as opposed to image in the sense of advertisement, shiny gleaming mirror. Other photo-realists seem more interested in images of this kind.

Ikon Gallery Birmingham is showing work by John Salt until 17 July 2011. I wandered through the two rooms of paintings, 18 in all, spanning 42 years of Salt's artistic output. Not wishing to be impressed (my mission, you may remember, is to view abstract paintings outside of London), I found myself confronted by a body of work that I was hugely impressed by.

I lingered longest on the 2001 painting Tree, a solitary vehicle, parked outside a disused store, next to a weedy self-seeded tree, the long shadows suggesting evening or morning.I feel it should be evening symbolically, but seeing how the windscreen is condensed it looks like it may be morning. The shadows emphasise the whereabouts of the cables running up the side of the building and bring attention to the puny tree, projecting a larger than life image of it onto the façade of the building, rather like the projected image of a photograph onto a large canvas, the standard technique for drawing in photo-realist art. The car and the store are a similar colour, terracotta, or rust. I think it highly unlikely that Salt is interested in the symbolic or metaphoric elements in the piece, and maybe these also are projections, but I find it difficult not to see in the terracotta, a symbol of rust and decay, also hinted at in the parked or abandoned car. And I find it difficult not to see in the tree at least a gesture of hope, however futile. I feel sure that this is not the content of the picture as far as the artist is concerned. However, I think the NLP mantra 'the meaning of a communication is the response you receive rather than the intention you had for it' applies here.

I found I could also interpret the painting in abstract 'colour-field' terms, enjoying the large expanse of orange, framed above by the light blue band of sky, and below by the darker blue/grey of the tarmac. Then becoming aware of the lemon yellow rectangle on the right hand edge, echoed by the adjacent dark grey or black rectangle of the door, within which is a cut-out of white. At the opposite side, there are similar rectangles in almost complementary colours of blue and lilac. In this reading of the painting the car plays almost no role at all. I realise that here I may have been compensating for the abstract paintings I did not find!

There are 18 paintings on view, shown more or less in chronological order, the first room with earlier work, paintings with images taken from catalogues, close-up cars, monochromes in red like Bride 1969, or grey like Sports Wagon 1969, the open door or window creating a frame through which to view the interior, and then the car wrecks of the early 70s: Falcon (Patchwork Surface) 1971, Desert Wreck, 1972; Pontiac with Tree Trunk, 1973. The second room has the more recent works, from the eighties to the present day, vehicles now more abandoned than wrecked, and shown in landscapes, usually a car or caravan, in its immediate surroundings.

At first I was frustrated at being unable to find much evidence of paint being worked or the artist's touch. I thought I had found actual brush-strokes in Falcon (Patchwork Surface). Did I have the impression here that the artist actually enjoyed painting the surface? Then, I realised that the the surface being worked was the car body, with spray-painted graffiti. Those painted gestures looked like they had been enjoyed! And then photographed and then painted, or rather airbrushed. I attempted to inspect the canvas edges for evidence of painterliness, only to be thwarted by the aluminium frames, tight to the stretcher.

Then, once I had resolved to stop messing about looking far what wasn't there and to enjoy the work for what it was, the first thing I noticed was the calm. Galleries are not noisy places, but these works seemed to elicit a quietness that was more than gallery quiet alone. I think it was my emotional state, rather than the physical environment. The paintings are still, still lives in a way, yet they are also memento mori, or as Dieter Roelstraete says in the gallery booklet "that type of still life that is much more eloquently rendered as nature morte". The Car not as status symbol,shiny and triumphant, but as wrecked, decaying, lonely or abandoned.

Although, according to the booklet, Salt claims not to be offering any social comment I agree with Roelstraete that it is difficult not to find here a comment on capitalism and its future. What I don't find is anything about imagined alternatives. I think I read somewhere in Zizek the criticism that we find it easier to imagine the destruction of the planet than we do to imagine a future alternative to global capitalism.

(John Salt, curated by Jonathan Watkins and Diana Stevenson, is showing at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, UK, until 17 July 2011)

Saturday, 18 June 2011

you cannot not?

Abstract painting is non representational, isn’t it? I remember when I first started to make abstract paintings, over 30 years ago that it seemed all about struggling not to represent. It was like the well known exercise where you sit next to someone and attempt not to communicate. Gregory Bateson used it to show that ‘you cannot not communicate’. There I was attempting not to represent, and everything I put down seemed to represent something. Even with a monochrome canvas, a vertical was a figure and a horizontal was a landscape. Here are, at least, figures on a ground.

Why do I find it pleasing that the pink ground becomes more like figure in the centre? And why was I less pleased when somone pointed out that the pink ground-become-figure can be read as a phallic symbol?

There is also autobiographical content hidden in the form. The scale had to do with my wealth or lack of it. When I had no money, the paintings were small or I painted over existing work. When I couldn't afford studio space, larger paintings were made by joining smaller stretchers together. When the paintings were monochromes what interested me were the subtle differences between virtually identical paintings. This had nothing at all to do with the fact that I am myself an identical twin. This was unrepresented, wasn’t it?

Why do I find it pleasing that the pink ground becomes more like figure in the centre? And why was I less pleased when somone pointed out that the pink ground-become-figure can be read as a phallic symbol?

There is also autobiographical content hidden in the form. The scale had to do with my wealth or lack of it. When I had no money, the paintings were small or I painted over existing work. When I couldn't afford studio space, larger paintings were made by joining smaller stretchers together. When the paintings were monochromes what interested me were the subtle differences between virtually identical paintings. This had nothing at all to do with the fact that I am myself an identical twin. This was unrepresented, wasn’t it?

Tuesday, 14 June 2011

Constructivism casts a shadow

At last I got to see the show Construction and its Shadow at Leeds Art Gallery, that I had seen on the Abstraktion blog a few weeks ago. I just made it, a week or so before it closed.

When I mentioned to the museum attendant how good I thought it was she seemed pleased that I liked it.

She said: "most people who comment say that it's rubbish".I was surprised by that, could it be that the fact of abstraction is still something of a shock for some? Yet here it didn't exactly seem new. The show felt like it was a reminder of a tradition.There was even that old museum smell (I like it).

I know it is still possible to hear it said of abstract painting that a child could have done it. But surely not this work. Most of it seemed complex, mathematical even (not easily done by children) and I would have thought difficult to dismiss.

It is a continuing quest of mine to see abstract art outside of London, so I had a good day in Leeds. At the Construction and its shadow exhibition I was particularly interested in the work by Jeffrey Steele. Later, I noticed that at the seminar I missed, about the influence of the British Constructivist and Systems groups, Jeffrey Steele had been speaking and I wished I had been there.

In the permanent collection of contemporary art I saw a Robyn Denny that I haven't seen for ages. When I saw it, I remembered hat I had seen it before, at Leeds many years ago. I also imagined that, back then I saw a big John Hoyland painting, but if I did it wasn't there today. (Just checking the catalogue I downloaded from the gallery website, there is a Hoyland in their collection. I would have liked to see that.)

There were three impressive John Walker paintings, as well as some by Terry Frost (not his best), and one by Gillian Ayres (Helios 1990, not my favourite). In the other collections, I particularly enjoyed looking at an Ivon Hitchens landscape.

When I mentioned to the museum attendant how good I thought it was she seemed pleased that I liked it.

She said: "most people who comment say that it's rubbish".I was surprised by that, could it be that the fact of abstraction is still something of a shock for some? Yet here it didn't exactly seem new. The show felt like it was a reminder of a tradition.There was even that old museum smell (I like it).

I know it is still possible to hear it said of abstract painting that a child could have done it. But surely not this work. Most of it seemed complex, mathematical even (not easily done by children) and I would have thought difficult to dismiss.

It is a continuing quest of mine to see abstract art outside of London, so I had a good day in Leeds. At the Construction and its shadow exhibition I was particularly interested in the work by Jeffrey Steele. Later, I noticed that at the seminar I missed, about the influence of the British Constructivist and Systems groups, Jeffrey Steele had been speaking and I wished I had been there.

In the permanent collection of contemporary art I saw a Robyn Denny that I haven't seen for ages. When I saw it, I remembered hat I had seen it before, at Leeds many years ago. I also imagined that, back then I saw a big John Hoyland painting, but if I did it wasn't there today. (Just checking the catalogue I downloaded from the gallery website, there is a Hoyland in their collection. I would have liked to see that.)

There were three impressive John Walker paintings, as well as some by Terry Frost (not his best), and one by Gillian Ayres (Helios 1990, not my favourite). In the other collections, I particularly enjoyed looking at an Ivon Hitchens landscape.

Monday, 13 June 2011

Integrating conscious and unconscious minds

In the wonderful big book Painting Today by Tony Godfrey, he says that

When I am working on small scale 'sketches' especially, I experience a relaxing of conscious control that I think, for me is an important element of this integration.

Making a painting is all about hand, eye and brain co-ordination: no other art form links mind and body so totally.I think this has similarities to Gregory Bateson's suggestion in Steps to an Ecology of Mind that

art integrates the reasons of the heart with the reasons of the reason, i.e. those multiple levels of mind "of which one extreme is called consciousness and the other the unconscious"?To co-ordinate mind and body and to integrate conscious and unconscious seem to me to be slightly different descriptions of the same thing. If I understand Stephen Gilligan correctly, he seems to identify cognitive mind with conscious mind, and somatic mind (body mind) with the unconscious.

When I am working on small scale 'sketches' especially, I experience a relaxing of conscious control that I think, for me is an important element of this integration.

Friday, 10 June 2011

Lost and found

From a series of small paintings, acrylic on paper, more or less a4 in size, all completed quickly, and many years ago. Recently, I had a dream reminding me where I had hidden them. Finding them, I discover that they seem to open up lots of new directions for larger paintings. I like the separation of time. Finding them now they seem like a gift from my unconscious or somatic mind.

Location:

United Kingdom

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)